We want to give you an inside look at our response to the COVID-19 crisis from the points of view of our incredible staff. They’ve been working together to keep people safe and supporting our patients and clients as they continue the difficult, daily work of recovery.

We’ve asked some of our team members at REACH and our opioid treatment program to reflect on their experiences during the crisis so far, what they are challenged by, how they’re taking care of themselves, and what good might come out of this.

Dr. Jamie Darnton is a primary care and internal medicine physician at Harborview Medical Center who works with our Flex Care program. Flex Care is an Office-Based Opioid Treatment program that allows patients to get a buprenorphine prescription from a doctor, increasing our capacity to treat people who cannot easily travel to a clinic.

During the crisis, Dr. Darnton has joined ETS’s committee on the infection control response. He has also been pulled in at Harborview on “surge deployments” or shifts to cover the needs around COVID-19, mostly working in their respiratory tent.

You can read more about how ETS is responding to the crisis on our dedicated COVID-19 Emergency Fund page.

Opioid addiction is a treatable chronic medical condition, like diabetes or hypertension, that causes changes in a person’s brain, manifesting as compulsive drug-seeking behavior despite harm. If a person with an opioid use disorder and active opioid dependence runs out of opioids, avoiding the dysphoria of withdrawal becomes the top priority to the exclusion of everything else. That’s why we sometimes see desperate or risky behaviors from otherwise intelligent, compassionate people.

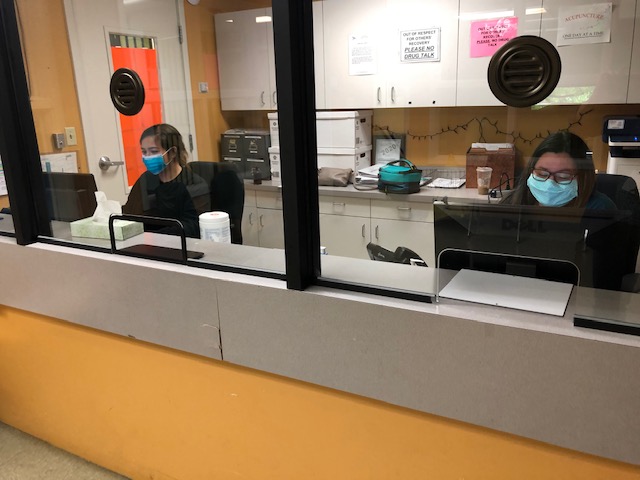

Within this context, there are many things that worry me about the intersection of the opioid epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic. Firstly, I’m worried about the health of our patients and staff, and of the surrounding community. Due to federal and state regulations, patients at opioid treatment programs need to attend the clinic in person every day for treatment for, at minimum, a period of many months. Patients gather from all over the county and have to wait—often in close quarters—for their daily medication. These patients then return to their homes, jobs, and communities and otherwise go about their lives. In this pandemic, this is clearly a problem. Opioid treatment programs that do not put effective infection control measures in place are at risk of facilitating disease transmission.

I’m also worried that treatment capacity may not be able to match demand. As the illicit opioid market is disrupted—which often happens during disasters—more people will likely seek treatment for opioid use disorder. At the same time, a lot of Office-Based Opioid Treatment programs and even some Opioid Treatment Programs are unable to perform intakes because of staffing shortages and infection control concerns.

We also know that using opioids in isolation is dangerous. If no one is around to witness an overdose, people are more likely to die. We spend a lot of time counseling patients not to use alone, but the mandates of social distancing make that advice much harder to follow. I’m worried that being disconnected from friends and family could both increase a person’s desire to use and ensure that they are alone when they do. It’s often said that the opposite of addiction is not sobriety, but connection— and it’s hard to maintain a connection to your community when everyone is self-isolating.

As you can see, there’s a lot to worry about with the intersection of the opioid epidemic and COVID-19. But the staff at ETS is an amazing, committed, and resourceful group. They’re going above and beyond to do the work that needs to be done. This team was able to put their heads together and find ways to serve patients and keep them safe. We’re limiting the number of people in the clinics at one time by allowing patients to take some of their medications at home, creating ways to efficiently enroll new people in treatment, and allowing patients who have COVID-19 symptoms to be treated outdoors and separately from patients without symptoms.

As you can see, there’s a lot to worry about with the intersection of the opioid epidemic and COVID-19. But the staff at ETS is an amazing, committed, and resourceful group. They’re going above and beyond to do the work that needs to be done. This team was able to put their heads together and find ways to serve patients and keep them safe. We’re limiting the number of people in the clinics at one time by allowing patients to take some of their medications at home, creating ways to efficiently enroll new people in treatment, and allowing patients who have COVID-19 symptoms to be treated outdoors and separately from patients without symptoms.

Since opioid treatment programs like ETS opened in the 70s, we’ve been studying medication-assisted treatment and know it is very effective at saving lives and creating the stability patients need to change their behaviors. The federal regulations around treatment, while providing the structure that some patients need in their recovery, create undue barriers for other patients. People with full-time jobs, no transportation, or people who do not have clinics nearby often cannot make it to treatment every day. Many of the regulations governing the function of OTPs are not based in clear science, and the changes ETS is making in response to the pandemic are exciting because they will allow us to begin to measure the safety and efficacy a treatment plan that is less prescriptive and more individualized.

We are hoping to leverage technology to better serve patients and keep them safe. We are using Telehealth technology to assess and treat patients remotely. We are also testing an app-based technology developed for monitoring adherence to tuberculosis medication that allows patients to video themselves taking their medications and communicate with their counselor. This app was piloted among a small group of patients taking buprenorphine at Harborview Medical Center and saw about 70 percent use with no negative patient reports. We are launching a pilot at ETS to see if this might be a helpful tool to keep patients safe and engaged in treatment, while at the same time allowing them to physically come into the clinic less often.

We’re going through a challenging time, and we have a lot of reasons to be concerned. But we also have a lot of cause for hope. I’m hopeful that some of the changes brought about by the pandemic on the functioning of opioid treatment programs and the treatment of opioid use disorder more generally, will allow us to find new ways to reduce barriers to treatment and improve quality of care. Wouldn’t it be great if one of the unintended outcomes of this pandemic is that our ability to treat people struggling with the opioid epidemic improves?